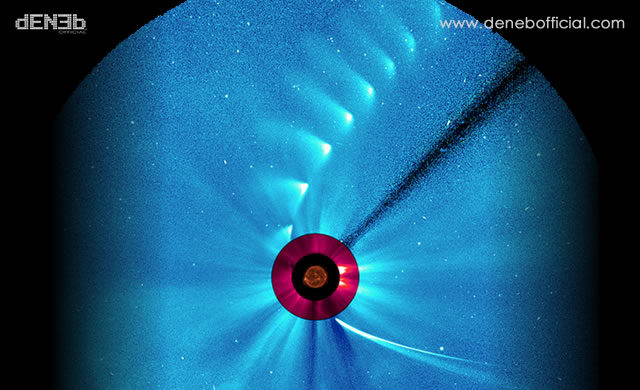

Image Credit: ESA/NASA/SOHO/SDO/GSFC

Dopo diversi giorni di osservazioni senza sosta gli scienziati continuano a lavorare per stabilire e comprendere il destino della cometa ISON: non c’è dubbio che la cometa si sia notevolmente ridotta in termini di dimensioni, smussata dal calore del sole e non c’è dubbio che qualcosa è comunque passato sul lato opposto della nostra stella per continuare la sua corsa nello spazio. Rimane da capire se il punto luminoso visto allontanarsi dal sole sia semplicemente un ammasso di detriti, o se un piccolo nucleo dell’oggetto originario di ghiaccio possa essere ancora presente in quello che è restato di ISON.

Indipendentemente da questo presupposto è probabile che al momento si possa trattare solo di polvere. La Cometa ISON, che ha iniziato il suo viaggio dalla Nube di Oort circa 3 milioni di anni fa, ha avuto il suo massimo avvicinamento al Sole il 28 novembre 2013. La cometa era visibile dagli strumenti del Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory della NASA (STEREO) e dallo strumento dell’Agenzia spaziale europea/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), attraverso immagini chiamate coronografi. I coronografi bloccano il sole ad una distanza considerevole intorno allo stesso per meglio osservare le strutture fioche nell’atmosfera solare, ovvero la corona. Attraverso tali strumenti c’è stato un periodo di diverse ore nel quale la cometa è stata oscurata dalla vista con il sole. Durante questo periodo di tempo, il Solar Dynamics Observatory della NASA non è stato in grado di vedere la cometa portando molti scienziati a supporre che la cometa si fosse disintegrata completamente. Tuttavia qualcosa è di fatto riapparso nelle immagini riprese successivamente dalle sonde SOHO e STEREO, anche se visibilmente meno brillante di quanto appariva poco prima. Se quella macchia di luce sia solo una nuvola di polvere, quello che potrebbe essere rimasto della luminosissima cometa, o se invece quell’oggetto osservato sia ancora provvisto di un nucleo, di una piccola porzione del cuore di ghiaccio originario ancora intatto, è ancora poco chiaro. Dalle osservazioni effettuate a partire dal 1 dicembre, sembrerebbe non esserci più traccia del nucleo. Monitorando le sue variazioni di luminosità nel corso del tempo, gli scienziati potranno stimare se effettivamente ci sia ancora un nucleo oppure no, ma la nostra migliore possibilità di ottenere informazioni certe sarà attraverso il telescopio spaziale Hubble nei prossimi giorni, durante questo mese di dicembre 2013. Indipendentemente dal suo destino, la cometa ISON non ha deluso i ricercatori. Nel corso dell’ultimo anno gli osservatori di tutto il mondo e nello spazio si sono riuniti per una delle più grandi serie di osservazioni di comete di tutti i tempi, i cui dati dovrebbero fornire materiale di studio per gli anni a venire. Il numero di osservazioni di ISON che comprende gli addetti ai lavori e gli amanti del cielo, gli astrofili e gli appassionati in genere, è senza precedenti, se consideriamo poi ben dodici attività spaziali della NASA attive dallo scorso anno.

After several days of continued observations, scientists continue to work to determine and to understand the fate of Comet ISON: There’s no doubt that the comet shrank in size considerably as it rounded the sun and there’s no doubt that something made it out on the other side to shoot back into space. The question remains as to whether the bright spot seen moving away from the sun was simply debris, or whether a small nucleus of the original ball of ice was still there.

Regardless, it is likely that it is now only dust. Comet ISON, which began its journey from the Oort Cloud some 3 million years ago, made its closest approach to the sun on Nov. 28, 2013. The comet was visible in instruments on NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory, or STEREO, and the joint European Space Agency/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO, via images called coronagraphs. Coronagraphs block out the sun and a considerable distance around it, in order to better observe the dim structures in the sun’s atmosphere, the corona. As such, there was a period of several hours when the comet was obscured in these images, blocked from view along with the sun. During this period of time, NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory could not see the comet, leading many scientists to surmise that the comet had disintegrated completely. However, something did reappear in SOHO and STEREO coronagraphs some time later – though it was significantly less bright. Whether that spot of light was merely a cloud of dust that once was a comet, or if it still had a nucleus – a small ball of its original, icy material – intact, is still unclear. It seems likely that as of Dec. 1, there was no nucleus left. By monitoring its changes in brightness over time, scientists can estimate whether there’s a nucleus or not, but our best chance at knowing for sure will be if the Hubble Space Telescope makes observations later in December 2013. Regardless of its fate, Comet ISON did not disappoint researchers. Over the last year, observatories around the world and in space gathered one of the largest sets of comet observations of all time, which should provide fodder for study for years to come. The number of space-based, ground-based, and amateur observations were unprecedented, with twelve NASA space-based assets observing over the past year.After several days of continued observations, scientists continue to work to determine and to understand the fate of Comet ISON: There’s no doubt that the comet shrank in size considerably as it rounded the sun and there’s no doubt that something made it out on the other side to shoot back into space. The question remains as to whether the bright spot seen moving away from the sun was simply debris, or whether a small nucleus of the original ball of ice was still there.

Source/Continue reading → NASA.gov