Una nuova immagine ottenuta all’Osservatorio di La Silla in Cile mostra il brillante ammasso stellare Messier 7. Facilmente visibile a occhio nudo vicino alla coda della costellazione dello Scorpione, è uno tra i maggiori ammassi aperti in cielo e un importante oggetto di ricerche astronomiche.

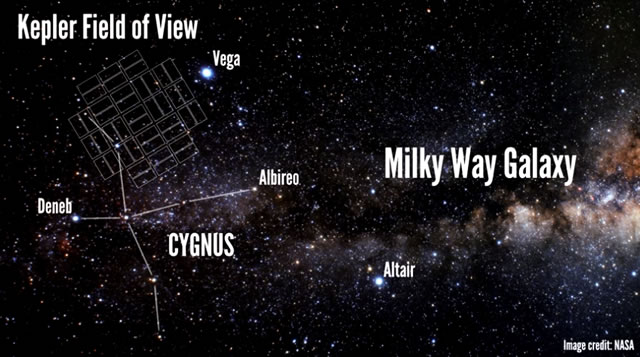

Messier 7, noto anche come NGC 6475, è un ammasso stellare brillante, composto da un centinaio di stelle a circa 800 anni luce dalla Terra. In questa nuova immagine ottenuta con lo strumento WFI (Wide Field Imager) montato sul telescopio da 2,2 metri dell’MPG/ESO si staglia su un ricco sfondo di centinaia di migliaia di stelle più deboli, nella direzione del centro della Via Lattea. Avendo circa 200 milioni di anni, Messier 7 è un tipico ammasso aperto di mezz’età e occupa una regione di circa 25 anni luce. Invecchiando, le stelle più luminose di questa fotografia – una popolazione che rappresenta circa un decimo di tutte le stelle dell’ammasso – esploderanno violentemente come supernove. Più in là nel futuro le altre stelle più deboli, molto più numerose, si allontaneranno lentamente le une dalle altre finchè non saranno più riconoscibili come un ammasso. Gli ammassi aperti come Messier 7 sono gruppi di stelle nate circa nello stesso momento e nello stesso luogo da grandi nubi cosmiche di gas e polvere nella galassia ospite. Questi gruppi di stelle sono molto interessanti per gli scienziati poichè le stelle hanno all’incirca la stessa età e la stessa composizione chimica e ciò le rende preziose per lo studio della struttura e dell’evoluzione stellare. Una caratteristica interessante di questa immagine è che, anche se fittamente popolato di stelle, lo sfondo non è uniforme ed è attraversato da strisce di polvere. Questo deriva probabilmente da un allineamento casuale tra l’ammasso e le nubi di polvere. Anche se si è tentati di ipotizzare che questi brandelli scuri siano i resti della nube da cui si è formato l’ammasso, la Via Lattea ha compiuto quasi una rotazione completa durante la vita di questo ammasso stellare, con conseguente riorganizzazione delle stelle e della polvere. Perciò la polvere e il gas da cui si è formato Messier 7 e l’ammasso stellare stesso si sono mossi da tempo per strade separate. Il primo a fare menzione di questo ammasso stellare è stato il matematico e astronomo Claudio Tolomeo, nell’anno 130 d.C., che l’ha descritto come una “nebulosa che segue l’aculeo dello Scorpione”: una descrizione accurata dato che, a occhio nudo, appare come una macchia diffusa di luce contro lo sfondo brillante della Via Lattea. In suo onore, Messier 7 è spesso chiamato l’ammasso di Tolomeo. Nel 1764 Charles Messier lo inserì come settimo elemento del suo catalogo omonimo. Più tardi, nel 19esimo secolo, John Herschel descrisse l’aspetto di questo oggetto visto attraverso il telescopio come un “ammasso di stelle grossolamente sparpagliate” – una perfetta descrizione.

Fonte/Leggi tutto → ESO.org

A new image from ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile shows the bright star cluster Messier 7. Easily spotted with the naked eye close to the tail of the constellation of Scorpius, it is one of the most prominent open clusters of stars in the sky — making it an important astronomical research target.

Messier 7, also known as NGC 6475, is a brilliant cluster of about 100 stars located some 800 light-years from Earth. In this new picture from the Wide Field Imager on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope it stands out against a very rich background of hundreds of thousands of fainter stars, in the direction of the centre of the Milky Way. At about 200 million years old, Messier 7 is a typical middle-aged open cluster, spanning a region of space about 25 light-years across. As they age, the brightest stars in the picture — a population of up to a tenth of the total stars in the cluster — will violently explode as supernovae. Looking further into the future, the remaining faint stars, which are much more numerous, will slowly drift apart until they become no longer recognisable as a cluster. Open star clusters like Messier 7 are groups of stars born at almost the same time and place, from large cosmic clouds of gas and dust in their host galaxy. These groups of stars are of great interest to scientists, because the stars in them have about the same age and chemical composition. This makes them invaluable for studying stellar structure and evolution. An interesting feature in this image is that, although densely populated with stars, the background is not uniform and is noticeably streaked with dust. This is most likely to be just a chance alignment of the cluster and the dust clouds. Although it is tempting to speculate that these dark shreds are the remnants of the cloud from which the cluster formed, the Milky Way will have made nearly one full rotation during the life of this star cluster, with a lot of reorganisation of the stars and dust as a result. So the dust and gas from which Messier 7 formed, and the star cluster itself, will have gone their separate ways long ago. The first to mention this star cluster was the mathematician and astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, as early as 130 AD, who described it as a “nebula following the sting of Scorpius”, an accurate description given that, to the naked eye, it appears as a diffuse luminous patch against the bright background of the Milky Way. In his honour, Messier 7 is sometimes called Ptolemy’s Cluster. In 1764 Charles Messier included it as the seventh entry in his Messier catalogue. Later, in the 19th century, John Herschel described the appearance of this object as seen through a telescope as a “coarsely scattered cluster of stars” — which sums it up perfectly.

Source/Continue reading → ESO.org