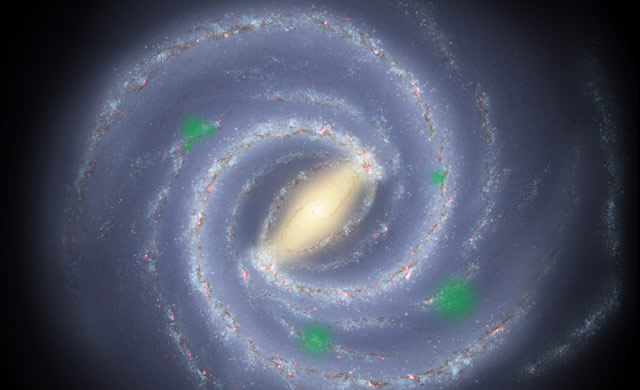

Abbiamo solo un esempio di pianeta con la vita: la Terra. Ma entro la prossima generazione dovrebbe diventare possibile rilevare segni di vita su pianeti in orbita attorno a stelle lontane. Se troviamo la vita aliena, sorgeranno nuove domande. Ad esempio, come ha fatto la vita a nascere spontaneamente? O potrebbe essersi diffusa da qualche altra parte? Se la vita ha attraversato l’abisso dello spazio interstellare molto tempo fa, come potremmo dirlo? Una nuova ricerca condotta da astrofisici di Harvard mostra che se la vita può viaggiare tra le stelle (un processo chiamato panspermia), potrebbe essersi diffusa in un modello caratteristico che potremmo potenzialmente identificare. “Nei nostri gruppi le teorie sulla formazione della vita crescono e si sovrappongono come bolle in una pentola di acqua bollente”, spiega l’autore Henry Lin dell’Harvard-Smithsonian Center per l’Astrofisica (CfA). Ci sono due modi di base per il diffondersi della vita al di là della sua stella ospite. Il primo attraverso processi naturali e gravitazionali come lo schianto di asteroidi o comete. La seconda modalità prevede l’intenzionalità per una forma di vita intelligente di viaggiare deliberatamente verso l’esterno. Lo studio non si occupa di come avviene la panspermia. Si chiede semplicemente: se si verifica, possiamo rilevarlo? In linea di principio, la risposta è sì.

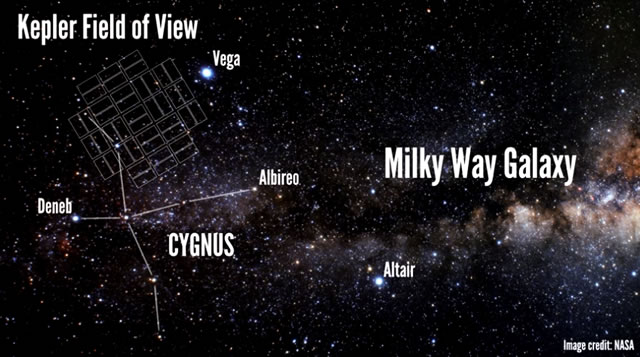

Il modello assume che i semi di un pianeta vivente si diffondono verso l’esterno in tutte le direzioni. Se un seme raggiunge un pianeta abitabile che orbita intorno a una stella vicina, là può mettere radici. Nel corso del tempo il risultato di questo processo sarebbe una serie di oasi create da portatori di vita che punteggiano il paesaggio galattico. “La vita potrebbe diffondersi dalla stella ospite ad un’altra in un modello simile a quello dello scoppio di un’epidemia. In un certo senso, la Via Lattea potrebbe essere “infettata” con tasche di vita”, spiega il co-autore CfA Avi Loeb. Se rileviamo segni di vita nelle atmosfere di mondi alieni, il prossimo passo sarà quello di cercare un modello. Ad esempio, in un caso ideale in cui la terra è sul bordo di una “bolla” di vita, tutti i vicini mondi che troveremo ospitanti la vita saranno in una metà del cielo, mentre l’altra metà sarà sterile. Lin e Loeb avvertono che un modello di questo tipo sarà rilevabile solo se la vita si diffonde piuttosto rapidamente. Poiché le stelle nella Via Lattea sono alla deriva una rispetto all’altra, stelle che sono vicine ora non saranno più vicine nell’arco di pochi milioni di anni. In altre parole, la deriva stellare potrebbe imbrattare le bolle. Questa ricerca è stata accettata per la pubblicazione su The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Con sede a Cambridge, Mass., l’Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) è una collaborazione tra la Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory e l’Harvard College Observatory. Scienziati CFA, organizzati in sei divisioni di ricerca, studiano l’origine, l’evoluzione e il destino ultimo dell’universo.

We only have one example of a planet with life: Earth. But within the next generation, it should become possible to detect signs of life on planets orbiting distant stars. If we find alien life, new questions will arise. For example, did that life arise spontaneously? Or could it have spread from elsewhere? If life crossed the vast gulf of interstellar space long ago, how would we tell? New research by Harvard astrophysicists shows that if life can travel between the stars (a process called panspermia), it would spread in a characteristic pattern that we could potentially identify. “In our theory clusters of life form, grow, and overlap like bubbles in a pot of boiling water,” says lead author Henry Lin of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

There are two basic ways for life to spread beyond its host star. The first would be via natural processes such as gravitational slingshotting of asteroids or comets. The second would be for intelligent life to deliberately travel outward. The paper does not deal with how panspermia occurs. It simply asks: if it does occur, could we detect it? In principle, the answer is yes. The model assumes that seeds from one living planet spread outward in all directions. If a seed reaches a habitable planet orbiting a neighboring star, it can take root. Over time, the result of this process would be a series of life-bearing oases dotting the galactic landscape. “Life could spread from host star to host star in a pattern similar to the outbreak of an epidemic. In a sense, the Milky Way galaxy would become infected with pockets of life,” explains CfA co-author Avi Loeb. If we detect signs of life in the atmospheres of alien worlds, the next step will be to look for a pattern. For example, in an ideal case where the Earth is on the edge of a “bubble” of life, all the nearby life-hosting worlds we find will be in one half of the sky, while the other half will be barren. Lin and Loeb caution that a pattern will only be discernible if life spreads somewhat rapidly. Since stars in the Milky Way drift relative to each other, stars that are neighbors now won’t be neighbors in a few million years. In other words, stellar drift would smear out the bubbles. This research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists, organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.

Source/Continue reading → www.cfa.harvard.edu