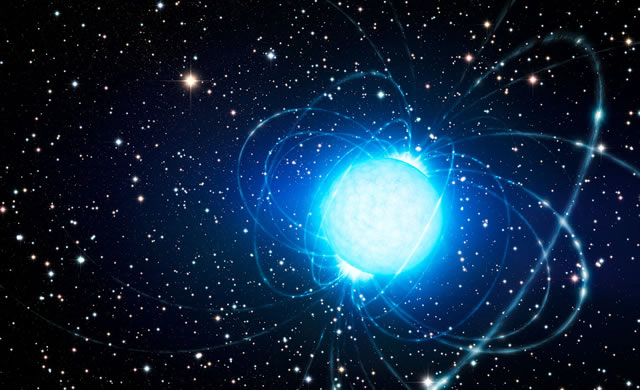

Le magnetar sono bizzarri resti super-densi delle esplosioni di supernova. Sono i magneti più potenti dell’universo – milioni di volte più potenti rispetto ai più potenti magneti sulla Terra. Un’equipe di astronomi europei, utilizzando il VLT (Very Large Telescope) dell’ESO crede ora di aver trovato per la prima volta la stella compagna di una magnetar. Questa scoperta aiuta a capire come si formino le magnetar – un rompicapo che dura da 35 anni – e perchè questa particolare stella non sia collassata in un buco nero come gli astronomi si aspettavano.

Quando una stella massiccia collassa sotto la propria gravità durante un’esplosione di supernova, forma o una stella di neutroni o un buco nero. Le magnetar sono una forma insolita e molto esotica di stelle di neutroni: come tutti questi strani oggetti sono piccole e straordinariamente dense – un cucchiaino di materia di una stella di neutroni avrebbe una massa di un miliardo di tonnellate – ma hanno anche un campo magnetico molto potente. La superficie di una magnetar rilascia grandi quantità di raggi gamma quando subisce un improvviso aggiustamento noto come “stelllamoto” (starquake) a causa dell’enorme sollecitazione nella crosta. L’ammasso stellare Westerlund 1, a circa 16 000 anni luce dalla Terra nella costellazione australe dell’Ara, contiene una delle circa venti magnetar note nella Via Lattea. Si chiama CXOU J164710.2-455216 ed è stata di grande sconcerto per gli astronomi. “Nel nostro lavoro precedente (eso1034) abbiamo dimostrato che la magnetar dell’ammasso Westerlund 1 (eso0510) deve essere nata dalla morte esplosiva di una stella di massa pari a circa 40 volte quella del Sole. Ma questa spiegazione hai i suoi problemi, poichè stelle così massicce dovrebbero collassare in un buco nero dopo la propria morte, non in una stella di neutroni. Non capivamo come avesse potuto diventare una magnetar”, dice Simon Clark, autore principale dell’articolo che descrive i risultati. Gli astronomi hanno proposto una soluzione a questo intrigo: hanno suggerito che la magnetar si è formata attraverso l’interazione di due stelle molto massicce in orbita l’una intorno all’altra in un sistema binario così compatto che sarebbe contenuto dall’orbita della Terra intorno al Sole. Ma finora nessuna compagna è stata rilevata alla posizione della magnetar in Westerlund 1, perciò gli astronomi hanno usato il VLT per cercarla in altre zone dell’ammasso. Cercavano una stella in fuga – oggetti che sfuggono dall’ammasso ad alta velocità – che avrebbe potuto essere stata cacciata fuori dalla sua orbita dall’esplosione di supernova che aveva formato la magnetar. È stata trovata una stella, Westerlund 1-5 che si comportava proprio così. “Non solo questa stella ha la velocità elevata che ci si aspetta dal rinculo di una esplosione di supernova, ma la combinazione di bassa massa, alta luminosità e composizione ricca di carbonio sembrano impossibili da replicare in una stella singola – un indizio schiacciante che mostra che originariamente si deve essere formata con una compagna in un sistema binario “, aggiunge Ben Ritchie (Open University), co-autore dell’articolo.

Fonte/Leggi tutto → ESO.org

Magnetars are the bizarre super-dense remnants of supernova explosions. They are the strongest magnets known in the Universe — millions of times more powerful than the strongest magnets on Earth. A team of European astronomers using ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) now believe they’ve found the partner star of a magnetar for the first time. This discovery helps to explain how magnetars form — a conundrum dating back 35 years — and why this particular star didn’t collapse into a black hole as astronomers would expect.

When a massive star collapses under its own gravity during a supernova explosion it forms either a neutron star or black hole. Magnetars are an unusual and very exotic form of neutron star. Like all of these strange objects they are tiny and extraordinarily dense — a teaspoon of neutron star material would have a mass of about a billion tonnes — but they also have extremely powerful magnetic fields. Magnetar surfaces release vast quantities of gamma rays when they undergo a sudden adjustment known as a starquake as a result of the huge stresses in their crusts. The Westerlund 1 star cluster [1], located 16 000 light-years away in the southern constellation of Ara (the Altar), hosts one of the two dozen magnetars known in the Milky Way. It is called CXOU J164710.2-455216 and it has greatly puzzled astronomers. “In our earlier work (eso1034) we showed that the magnetar in the cluster Westerlund 1 (eso0510) must have been born in the explosive death of a star about 40 times as massive as the Sun. But this presents its own problem, since stars this massive are expected to collapse to form black holes after their deaths, not neutron stars. We did not understand how it could have become a magnetar,” says Simon Clark, lead author of the paper reporting these results. Astronomers proposed a solution to this mystery. They suggested that the magnetar formed through the interactions of two very massive stars orbiting one another in a binary system so compact that it would fit within the orbit of the Earth around the Sun. But, up to now, no companion star was detected at the location of the magnetar in Westerlund 1, so astronomers used the VLT to search for it in other parts of the cluster. They hunted for runaway stars — objects escaping the cluster at high velocities — that might have been kicked out of orbit by the supernova explosion that formed the magnetar. One star, known as Westerlund 1-5 [2], was found to be doing just that. “Not only does this star have the high velocity expected if it is recoiling from a supernova explosion, but the combination of its low mass, high luminosity and carbon-rich composition appear impossible to replicate in a single star — a smoking gun that shows it must have originally formed with a binary companion,” adds Ben Ritchie (Open University), a co-author on the new paper.

Source/Continue reading → ESO.org